Late modernist mass housing estates and micro-district planning marked a significant milestone in the development of Ukrainian cities. Kharkiv and Zaporizhzhia served as key platforms for urban planning experiments. However, since the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, these residential areas have been subjected to relentless artillery shelling. During post-soviet transformations, residential complexes have faced multiple challenges. Today, their damaged state is often framed not as a preservation concern, but as an opportunity for introducing experimental reconstruction technologies—frequently without serious consideration for the architectural or social value of the existing structures.

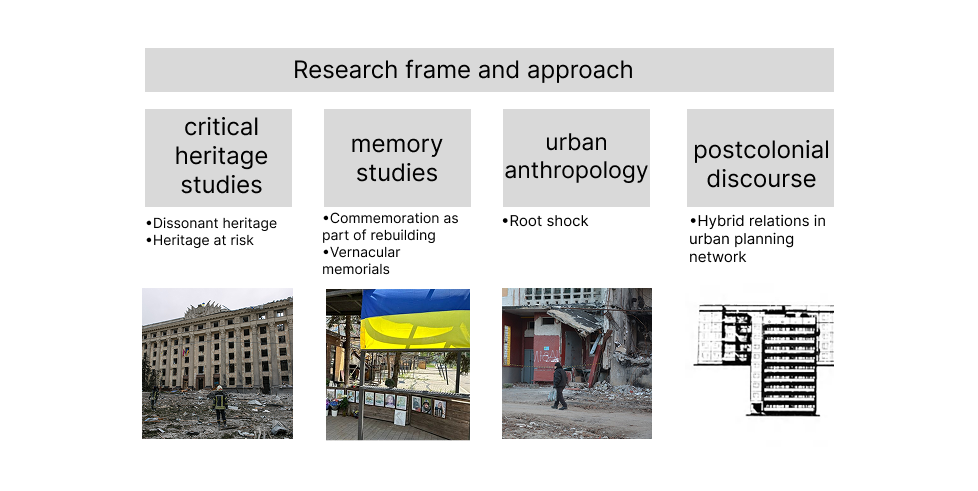

This project approaches the current situation through the lens of critical heritage studies, with a focus on the concept of dissonant heritage. In recent years, perceptions of Soviet architectural heritage have evolved into a nuanced hierarchy. While interwar modernism has been somewhat integrated into Ukraine’s urban history as part of the so-called Red Renaissance, Stalinist-era architecture is largely demonized. Late modernism, meanwhile, remains either negatively perceived—classified under totalitarian architecture—or entirely disregarded as heritage. In practice, decommunization efforts often involve removing Soviet-era symbols from architectural objects, sometimes without the necessary permits or approvals from heritage protection authorities, leading to conflicts with established preservation principles. As relatively “young” heritage, these structures lack formal legal protection and are thus especially vulnerable to demolition or radical transformation. This contested status reveals much about how Ukrainian society is negotiating with the Soviet past, and how this heritage might—or might not—be integrated into future urban strategies.

In addition to heritage studies, the project draws on urban anthropology to investigate everyday experiences within these districts, both past and present. On one level, we examine how residents have adapted these spaces to make them more comfortable for living—through informal modifications, community initiatives, and personal investment. On another note, we consider the impact of trauma and displacement, especially during the spring of 2022, when many inhabitants survived under siege. These testimonies can inform not only research but also future commemorative practices. The concept of "root shock," introduced by social psychiatrist Mindy Thompson Fullilove, is particularly relevant here. It captures the profound psychological and social dislocation caused by the sudden loss of familiar environments—a phenomenon now experienced by many residents of these estates.

The project consists of two interlinked parts. The first investigates the planning logics and institutional structures behind Soviet-era urban development. Through archival research we aim to trace how decisions were made, by whom, and in what institutional context. This opens space for engaging with postcolonial perspectives: were these planning processes shaped by center-periphery dynamics? Were they colonial, hybrid, or something else entirely? These questions help situate late modernist estates within broader debates about totalitarianism, imperial legacies, and national identity.

The second part focuses on the contemporary challenges surrounding this architectural heritage. What values—tangible or intangible—are associated with these spaces today? How are they represented, preserved, or erased in current rebuilding processes? On the one hand, as mentioned before, the late housing estate is not recognised as heritage within authorised heritage discourse for various reasons. On the other hand, we see attempts to apply non-tangible values, such as way of living, community building, local identity both by researchers and activists. The experience of survival during wartime has further enhanced their potential memorial significance.

A key question here is: Who gets to define the future of these spaces? The project maps out how different actors—professionals, activists, residents, institutions—perceive Soviet-era housing and what roles they play in shaping its reconstruction. It investigates how heritage discourses influence planning decisions, and how bottom-up practices of commemoration, participation, and care intersect with official rebuilding efforts.

Ultimately, the project seeks to understand the shifting narratives that underpin the reconstruction of Ukrainian urban fabric. Rather than imposing a single viewpoint, we aim to foreground the diverse and sometimes conflicting voices involved in shaping postwar urban futures.